PERUCETUS COLOSSUS: REMAINS OF THE HEAVIEST ANIMAL THAT EVER LIVED ON EARTH DISCOVERED IN PERU

The new finding of Peruvian paleontologist Mario Urbina turned out to be the heaviest animal that inhabited the earth. This has been baptized as Perucetus colossus (the Peruvian cetacean colossus) and the discovery was published in the prestigious journal Nature on August 2nd. This article had the participation of researchers from different parts of the world, among them Dr. Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi, professor of our university.

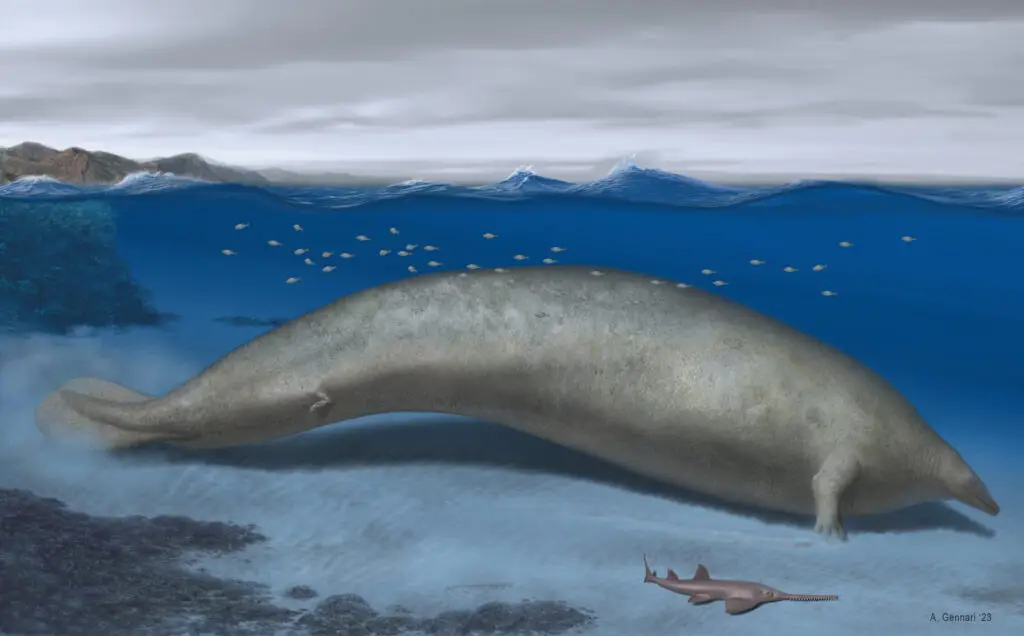

Perucetus colossus was a primitive cetacean of the Basilosauridae group that inhabited the coasts of Peru during the middle Eocene, about 39 million years ago. It is estimated that it reached 20 meters in length and weighed about 199 tons, making it the heaviest animal ever to inhabit the Earth. Its bones are highly modified in relation to other animals, due to the fact that they acquired an enormous density and a huge volume. Some aquatic animals have this type of characteristic, but it was not known that they had reached such extreme values. Nor was it known that in the Eocene, a warm period of the planet, the seas could provide sufficient resources for an animal of the magnitude of Perucetus to evolve.

The first vertebrae were discovered by Mario Urbina in 2013 while he was walking in the Samaca area (Ica desert), searching for primitive cetacean remains. Mario took several scientists to identify the fossil, but the peculiar characteristics of its shape, as well as the extreme density of the bone, generated many interpretations to the point that some thought it was not even bone. Mario was convinced that it was a gigantic unknown cetacean and time proved him right. After ten years, the extraordinary fossil was published by Peruvian and foreign scientists in Nature, the most prestigious scientific journal in the world, under the name of Perucetus colossus, for being the heaviest animal of all time. The discovered material (MUSM 3248) consists of 13 vertebrae, four ribs and part of the pelvis. The rest of the skeleton is unknown.

Perucetus has been so named in honor of Peru, as it confirms that the fossil record of the Peruvian territory is one of the most valuable and important in the world in marine animals.

(Leyenda de foto)

The remains were discovered in rocks 39 million years old in the Ica desert.

How do we know it was one of the heaviest animals of all time?

Increased bone density is observed in several animals that inhabit shallow water and feed on bottom-dwelling organisms, such as sirenians, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, etc. However, the bones of Perucetus colossus exhibit the greatest degree of density and volume increase known for any animal that has ever lived on Earth, aquatic or terrestrial. This means that the bone is almost entirely compact, unlike the porous bones possessed by all animals. In addition, the volume of its bones is 350% greater than that of other basilosaurs.

Because skeletal weight in aquatic mammals is a fraction of total weight that varies between certain ranges, it has been estimated that Perucetus may have weighed 199 tons, more than the blue whale (130-150 tons) or the gigantic Argentinosaurus (~50-100 tons). Prior to the discovery of Perucetus, animals were not known to have reached such magnitudes.

For these studies, three-dimensional models of each of the bones were created using a laser scanner. With this information and a series of computational regressions (statistical analyses), the team estimates a live weight of Perucetus with a minimum of 86 tons and a maximum of 340, on average about 199 tons.

What was its food?

As neither the skull nor the teeth of Perucetus have been discovered, we do not know what it fed on. However, due to the density of its bones, it is thought that it was a coastal animal that lived near the bottom in shallow waters. It probably fed on benthic animals, i.e., those that live associated with the bottom, such as crustaceans, mollusks or fish. There is also the possibility that it may have been herbivorous, although in this case, it would be the only known herbivorous cetacean.

How was the specimen collected?

As each Perucetus vertebra weighs about 150 kg, Mario Urbina led dozens of expeditions to collect one to two of them. The first vertebrae could be seen on the surface of the desert, but the rest were buried inside a hill, which had to be removed with hammers to break concrete. The collection team consisted of Walter Aguirre, Alfredo and Beder Martinez, Eusebio Diaz, Joan Chauca and other members of the Vertebrate Paleontology Department of the Natural History Museum-UNMSM.

For more than 25 years, Peruvian paleontologist Mario Urbina has traveled the desert between Ica and Arequipa in search of fossils that document the history of the ancient Peruvian sea. Some of his most outstanding finds include the only legged cetacean discovered in South America, Peregocetus pacificus; the toothed whale Mystacodon selenensis; and dozens of other important fossils among cetaceans, crocodiles, sloths, seals, penguins, etc.

The scientists The international team that participated in the Nature publication is composed of Giovanni Bianucci (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, Italy), Olivier Lambert (Royal Institute of Natural Sciences of Belgium, Belgium), Marco Merella (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, Italy), Alberto Collareta (Department of Earth Sciences, University of Pisa, Italy), Rebecca Bennion (University of Liege, Belgium), Klaas Post (Museum of Natural History Rotterdam, The Netherlands), Christian de Muizon (Museum of Natural History of Paris, France), Giulia Bosio (University of Milan-Bicocca, Italy), Klaas Post (Natural History Museum of Rotterdam, The Netherlands), Christian de Muizon (Natural History Museum of Paris, France), Giulia Bosio (University of Milan-Bicocca, Italy), Claudio Di Celma (University of Camerino, Italy), Elisa Malinverno (University of Milan-Bicocca, Italy), Pietro Pierantoni (University of Camerino, Italy), Igor Villa (University of Bern, Switzerland) & Eli Amson (Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History, Stuttgart, Germany). In addition, Peruvian paleontologists Mario Urbina (Museo de Historia Natural UNMSM), Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi (Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia) and Aldo Benites-Palomino (University of Zurich and Museo de Historia Natural-UNMSM).